April 18I meet Christian for lunch, my first real restaurant meal in India. Somehow I spend 200 rupees ($4.75) which is lot. I want to go south or east, Christian wants to go north or east, so we decide to head east together.

At the Jaipur train station there are a thousand people waiting for tickets. Thankfully we can get in the line for Tourists/Senior Citizens/Handicapped/Freedom Fighters. (No, we don’t know who Freedom Fighters are). There are about four people in front of us in line and it takes a little less than an hour to get to the window. The train is full but we get on the wait list.

In the meantime we walk around the markets. The touts are well concentrated here. Out of nowhere a bike pulls up with a 17-year old guy on it. “Why don’t tourists talk to Indians?” he asks.

“Well I think they don’t talk to Indians because sometimes it seems like everyone who talks to you wants something from you.” He gets off the bike as I start to answer.

“You think we’re all beggars,” he says. “We go to school all day and then in the afternoon our only way to practice English is to talk to the Europeans but they won’t talk to us. Why won’t you talk to us?”

“Well I’m talking to you right now so you can’t say I won’t talk to you.”

“I have a friend in Europe and I want to write him a letter but I don’t know how to write in English, will you write it in English for me?”

“Do you have the letter?”

“It’s up in that building. We’ll go up there and you can write it.”

I start to question the whole thing. “Sorry, I can’t. If you had it here I would but I can’t go up there.”

“Every time the Europeans say ‘Oh, I’m too busy, I have to go, I can’t help you.’ It would only take a minute.” He gets back on the bike with his friends. “You should go back to your country and leave India.”

Then as Christian and I walk down the street his friends on the bike follow us for a long time and ask us to go up to the same building that had the letter to translate. It has a great view, they tell us, you can see the whole city. And maybe it has a jewelry store we can look at too.

I come to learn the central problem of visiting India is how de-humanizing it becomes. In a vicious cycle the tourists treat the Indians badly and locals treat the tourists badly. They aren’t people, they’re just voices trying to sell you things or wallets with a lot more money in them than your life savings. There’s no getting around this conflict and it makes meaningful interaction rare and difficult.

After a couple hours in the markets we go back to the train station and learn we didn’t get tickets for the train. We walk a mile-plus to the bus station and buy tickets to Agra, home of the Taj Mahal.

I say goodbye to the Saxena family and meet Christian for our 11pm bus. The “luxury” buses here lack toilets which is a problem for Christian who is having some trouble with his stomach. “Trouble with his stomach,” is such a nice way to put it. Other than one day of feeling a bit achy, I haven’t had any trouble eating street food or drinking things with ice or brushing my teeth with the water or any of the other things that super concerned travelers avoid.

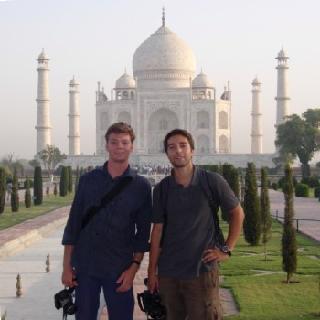

April 19The bus gets into Agra around 5am and we head to the Taj Mahal. We get there just in time for sunrise. The entrance fee is 20 rupees. Or, if you’re a foreigner it’s 750. Yikes. They know you’ll pay and you do and it’s worth it. We take about a hundred pictures of each other and then finally go look at the thing. It is impressive, remarkably symmetrical and surprisingly small in the central room under the dome where the King and Queen’s tombs are. My favorite place is under the dome, about 10 feet behind the tombs. You can look back out the door and through the various gates that lead to the main building; everything lines up perfectly all the way to the horizon half a mile away.

Three hours is enough of that and since there isn’t much in Agra after the Taj we start looking for a train ticket. We find a “part-time travel agent” who says he can find out if there are seats available if we go to his office. When we refuse to go there he says he can make a call from “his jewelry store.” So we go there and he makes some calls and says we can’t get on the 8:30pm train but there are seats on the 11:30pm. He doesn’t know how much the ticket will be but he’ll charge us a flat 75-rupee commission regardless. We have a lot of trouble knowing whether to trust him. He says the train is booked (which is likely) but through a special agent he can get us tickets (somewhat less likely). We give him 200 rupees each and are told to come back at 1pm to get our tickets and pay the balance. It seems shady but at the end of the day it’s only $5 and the other choice is an excruciating hunt around town to the train and bus stations.

We return at 2pm and the shop is closed; supposedly the guy is at Mosque. We return at 3pm, this time with the video camera. I figure if we don’t get the tickets we’ll at least get a cool segment for the documentary. Christian and I are playing everyone’s favorite Indian travel game: “Scam or Not a Scam.” This time the guy isn’t there but another guy is in the shop and after leaving to make a phone call he says the “part time travel agent” is picking up the tickets and we should come back at 4pm. It’s impossible to say if bringing the camera to the shop helped produce the tickets but at 4pm the tickets were there. With commission we pay 281 rupees each which was a bit high but pretty reasonable given the short notice.

The guy is very offended that we would think he was scamming us.

We sleep in transit for a second straight night, this time in the sleeper class of the train. Imagine what you think the sleeper class of an Indian train might look like and that’s what it looks like. If you’re imagining chickens in the isles you’ve gone too far. Have you ever taken a tour of a submarine and they show you the stacks of tiny beds the sailors sleep on? That’s kind of what it’s like.

The best part of the “part time travel agent’s” arrangements for us was that we got to change trains at 4am. It wasn’t clear if we actually had seats on the second train and everyone we showed our tickets to got these confused looks on their faces, then laughed a bit. “I’m suspicious of your ticket,” a seatmate told us. “It is good for this train but for the second train you should re-confirm. You may have to buy a second ticket.”

An Indian train station at 4am is a certain thing. The floors are covered with people sleeping. It’s predawn. You don’t know where your train is or if you have the right ticket to get on it. You’re still in your pajama pants as you walk through the station getting shouted at by touts.

The guy at the info desk offers to sell you “supplemental tickets” for the connection train for 20 rupees each. That seems like a scam too.

So we get on the second train and take the same seats we had for the first train even though we know this is wishful thinking. Eventually the conductor checks our tickets and says they aren’t confirmed. We play dumb and he lets us share a seat (instead of the sleeper births we were supposed to have).

April 20At 8am we pull into Allahabad. More than any other day of the trip, this day encapsulated the good and bad that makes India what it is.

Christian has a friend who has a friend who lives here and he called up the night before to say we’d be coming in around 6am. “Okay, I’ll pick you up at the train station,” the stranger said. We called a little after 5am to tell him we’d really be there at 8am. He didn’t seem to mind.

“The lawyer,” as we came to call him because we forgot his name, drove us to his home and served us breakfast. We’d leave our bags at his house for the day while we explored Allahabad then pick them up in the evening before getting on another bus.

His wife insisted on serving us breakfast. She was about 25 and he was about 35. They have a one-year-old daughter. You forget most Indian couples are products of arranged marriages because they seem like happy, normal families. This pair reminded me they were arranged. It seemed more like a business relationship than a personal one.

There’s a growing trend of “love marriages” here now. It’s still a somewhat exotic concept but Muhammad, my 20-year-old auto-rickshaw driver in Jaipur told me he had a girlfriend of two years who he planned to marry. Erika, the girl I flew here with, said her and her boyfriend are constantly approached on the street with the question “Love marriage?”

Christian and I left the lawyers house for one of the more bizarre encounters of my trip. Christian’s reason for coming to Allahabad was to visit a “Trees for Life” school here. Trees for Life is a volunteer educational organization that he worked for a couple years ago. He wanted to see their program here. Turns out the school wasn’t really a part of Trees for Life but we were committed to going by this point.

We walked into the courtyard of the school and a guard called us over and offered us chairs. Then he took us into the principal’s office and Christian said he had worked for Trees for Life and would like a tour. So they brought us around the mostly girls elementary school and we got stared at a lot. Everyone was wearing white shirts under powder blue dresses. When the principal walked into a class all the students would stand up at attention, giggle, look or point at us, then be told to sit down. I tried extremely hard not to laugh and did my best to ask interested questions. It was interesting.

We took an auto-rickshaw into City Lines, the main town here. It’s funny to use words like town to describe a place with a million people but the numbers are all so large here that a place with a million residents doesn’t feel so big.

It was damn hot. You know in the summer when you park your car in the sun with all the windows rolled up and then a couple hours later you get back in? That’s how it felt today. It felt exactly like that except you didn’t burn your butt on the seat. Christian and I were eating mangoes at a stand in City Lines when a building caught on fire. It was right across the street and the flames were pouring out of the porch area of the second floor apartment. Big fireballs would flare up now and then. Eventually it went out.

We asked a bookshop owner for a good, cheap place to eat and he came up with a recommendation. Instead of giving directions he sent a guide with us. There is so much cheap service labor here that people are constantly being used for things that don’t really require people. So the bookshop owner sent an employee to walk us five minutes down the street to a little hole in the wall restaurant.

There were lots of looks and laughs as we sat down. At places like this there generally isn’t a menu and you just order “a plate.” This ran counter to Christian’s celebrity-style ordering habits which call for substitutions or off-menu ordering even when the waiter speaks little English. The meals were good and cost 20 rupees.

It was around this time that India got annoying. It’s not the heat, or the hassling touts, or the risk of fraud that makes India so difficult. It’s the totally unrelenting nature of all these things. It’s hot every damn minute. There is always, always, always someone shouting “Where do you go? Auto-rickshaw! Take a look. Sir? Sir? Auto-rickshaw. Where you going? Come here sir. Take a look!” You want to relax and you can’t.

We couldn’t find an auto-rickshaw so we settled for bike rickshaws. They’re man-powered bicycles with little carriages in back. Christian and I each took our own to reduce weight and spread the wealth. The price was 10 rupees. The half-hour ride was an adventure. It is serious manual work to peddle that thing in the heat across town and my driver wasn’t a young man.

We reached sangam, the sacred confluence of the Ganges and Yumana rivers where in a single day (each January or February) 10 million pilgrims flood the meeting point. The rickshaw drivers refused our 10 rupee notes and the one English speaker in the encircling group explained they were demanding 60 rupees each. There was much shouting about where we had started the trip and what the agreed price was and eventually we agreed to 15 rupees each. We needed to pay with a 50 rupee note but my driver didn’t produce the agreed upon change so our only recourse was not to pay the other driver, forcing him to get his money from my guy. So they got 25 each instead of ten.

“They cheated you,” the English speaker said as he followed us, uninvited, towards the rivers. At sangam there were about two hundred boats waiting to carry tourists out to where the rivers meet. There were two tourists. One problem with traveling in low season is there are fewer fellow tourists but the same number of locals hoping to earn a living off the tourists. You don’t count how many times people offer you a boat trip during the 15 minute walk but if you did it would be around a hundred and feel like much more.

At the river people were bathing and out in the distance where all the boats were crowded I could kind of see the murky Ganges meeting the clearer Yumana. I met Vikteen, a middle-aged man, at the river. “What country?” he asked, in the traditional greeting of a foreigner.

“USA,” I said.

He lived in Allahabad and was a doctor. Many of his classmates moved to the US to practice medicine but he liked it better here. I asked him how often he came to sangam. “Once or twice a year,” he said. “How often do you go to Central Park?”

“I live one block from Central Park so I go there all the time.”

“Well then how often do you go to the Statue of Liberty. Not see it on TV or the movies but go there and see it.”

“Very rarely. I’ve only been to the actual Statue once.”

“Well it is the same. When you live very close to a place you don’t go often, it becomes normal to you.”

Vikteen explained that 50 years ago the pilgrims would march up to 500 kilometers on foot for the big festival here. They’d make a single-file line that stretched all the way from the river down to the south of the country. Now everyone drives and the banks on the far side serve as a parking lot.

Christian and I walked back to where the rickshaws were and the English speaker was still following us. We asked him to leave us alone but he wouldn’t. Eventually we negotiated the ride from 100 to 40 rupees and headed back to the lawyer’s house. When he dropped us off the driver asked for more money (they always do) but we wouldn’t give him the 50-rupee note until he produced the 10 rupees in change. Lesson learned.

We get on another evening bus for Varanasi, one of the most holy places in Hinduism. It leaves at 7pm and arrives around 10:30pm. It’s a local-style bus filled with commuters, some of them standing. The seats are less than shoulder-width wide. Sometimes you step back from the situation and realize you’re in one of the more remote, adventurous travel situations the world offers but it feels less exotic than you’d think. “Yeah,” Christian agreed as we sat at the Ganges earlier that day. “You think it should feel different and it will be like a different world but you realize how much the same it is, how small the world is.”

It feels exotic enough in Varanasi, where the Lonely Planet informs “two or three travelers go missing in the city every three or four months.” Apparently they’re abducted from the airport/train station/bus station. So we take our 11pm auto-rickshaw through the empty streets to Assi Ghat. We can’t tell the rickshaw driver where we’re staying because then he’ll get a commission from the guesthouse and the cost will be passed on to us. So we get off in the middle of the neighborhood and try to find out where the Sahi River View Guest House is while the auto-rickshaw driver keeps following us. Eventually we find it up a long, dark, scary ally and ring the buzzer. A sleeping guard/receptionist unlocks the doors and lets us in. It’s the first night in a bed since Jaipur.