October 26

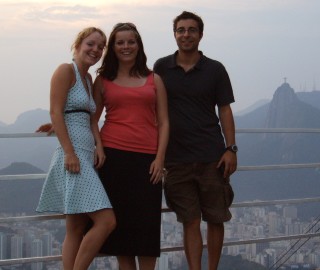

October 26No one told Lonnie and Tania that the plan for South America was to stop writing about girls. So they got on the bus at the airport and followed me to Ipanema and set out to intrude on the story of Rio. I’ll do my best not to let them.

First Acai. Theres is a little dangly thing below the “c” in acai so you pronounce it like an “s.” I’ve never seen this native fruit but I taste it almost every day in the form of a thick fruit shake. It’s the color of a brightly lit red wine and manages to taste like a mix of blackberries and chocolate without really tasting much like either.

There was little physical need for refreshing drinks this first week in Brazil because it was so often cloudy. In the sunny stretches we went to the beach and otherwise Tania and I would play 500-rummy using her crazy Danish rules or Lonnie and I would trade massages in our poorly ventilated dorm room and all the while I would remind myself that the plan for South America was to stop writing about girls.

So on Saturday we decided to Samba in the

favela. Samba schools spend their year building up to one event: Carnaval. That’s when the kids from the

favela become the object of all the tourists’ attention as they dance down the street in their Technicolor outfits. On the third Saturday night in October the schools choose their Carnaval song. That was this Saturday.

Nicholas is Brazilian and sleeps in the bunk above me. He’s been in Rio for three months while the bank he works for back in Brasilia is on strike. Picturing long-haired, groovy, perpetually undressed Nicholas working in a bank is like imagining Bill Gates in a Speedo on the beach. (And in conjuring that image, I wonder whether Gates would keep his oval glasses on or spring for contacts or even lasik. But I digress.)

The nice thing about having a crazy Brazilian in your room is he speaks Portuguese. So the Danish girls, Nicholas and I decided to walk up towards the

favela around 1am Saturday night to watch some Samba.

The next morning we told the guy at reception what we’d done.

“Who did you go with?”

“Well it was the four of us.”

“You didn’t go with someone from the

favela?!”

“No, just Nicholas, he speaks Portuguese.”

“Well that was really stupid,” he said, walking away. “That was really, really stupid.”

Nicholas wasn’t sure just how to get to the

favela and Lonnie had told me earlier that Tania was worried about the whole thing. I was too, quite honestly. As we walked up the long, steep hill that leads to the slum we passed only two other walkers—young, dark skinned men—and a handful of speeding cabs. The streets were bare.

“This is a good workout,” Tania said, but it was unclear if it was the incline or the destination that had raised our pulses.

We reached a fork in the road and Nicholas asked the man at the little outdoor bar there, ‘Which way to the samba?’ As they spoke a couple women looked over at the girls and shook their heads.

“I think those ladies are telling us not to go up there,” Tania said to Nicholas.

“No, I was asking if they were charging an entrance fee,” Nicholas said. “They were saying, ‘No,’ there’s not charge.”

“Oh. Good.”

At the top of the final hill the street exploded with life and music. People were out on their front steps, rushing across the street, talking excitedly and generally having a good lively Saturday night.

We walked up a flight of stairs to the open-air dance hall and the music came blaring at us. At first there was no stage, just a clot of men banging drums in the center of the room and well-toned women dancing near them. There were young men in drum-major uniforms dancing with them too. They were informally surrounded by a crowd of spectators.

It was too loud to talk but we worked our way through the crowd and then we could see the stage where a couple men shouted out the lyrics through the powerful, crappy sound system.

“This is their only entertainment,” Nicholas said. “They don’t have money to go out anywhere, so this is it for them in their community.”

What strikes me in the

favelas is how well dressed everyone is. This could be a reflection of my diminished expectations for a wardrobe (most of my clothes have gaping holes in them) or my experience with the poor in Asia who seemed more obviously desperate. Whatever the case, I happened to wear my best outfit (jeans and a polo) and was not over-dressed. Only my fancy digital watch was out of place.

If you were to travel around the world and could pick only one country to physically blend in with the population, Brazil might be the best choice. Heredity made that choice for me—my ancestry is largely Brazilian-Portuguese—and though I can’t speak ten words of the language I’ve had a strange sense of fitting in here. But the camouflage faded away in the

favela where skin tones turn several shades darker.

Lonnie wore a hat to cover her long, light-blonde hair. But she couldn’t cover her fair skin or Tania’s crystal eyes and we were obvious outsiders. There was one other foreign woman in the crowd, a middle-aged blonde from California.

We don’t know which song was chosen for Carnaval because after two of the five nominations had been performed it was nearing 3am and we were tired. We walked back down the hill towards affluence and made it to the hostel unharmed.

Let me tell you a few more things about Rio. When we got to the hostel the night guard was sleeping. He sits on the porch outside our building from 10pm til morning because Rio is a dangerous city. It’s also a city with strict noise regulations and so his other job is to keep the backpackers quiet after 10pm. Even talking in a whisper outside our building is forbidden.

It’s a strange contrast to Lapa, where the noise is considerable until the sun comes back up. That’s where we spent our Friday night. Me and the Danish girls—still angling to earn further mention with each warm smile and short skirt—took a taxi to Lapa just after midnight. The cab dropped us in the middle of a throbbing outdoor blockparty. A couple thousand revelers were drinking or smoking or talking in the streets and the neighboring park and outside the loud clubs. Alcohol consumption is the mother of entrepreneurialism and along the street people had set up tiny, flimsy outdoor bars. They peddled cans of beer and even

caipirinhas, the powerful Brazilian sugar-cane cocktail. One

caipirinha is less than a dollar, two

caipirinhas are all you’ll need.

“I’m really glad you’re here with us,” Lonnie said. It wasn’t a sentiment of affection as much as protection and I felt a strange chivalrous impulse to shield the Danes from abduction or assault.

There was no such danger until five that morning. We were waiting for the bus at that point, which indicates we had enough

caipirinhas to think it was a good idea to take the bus. But we weren’t too drunk to notice the guy with the tall ‘fro reaching into Tania’s pocket. We made a little noise and stepped a few feet away and then got on the bus towards Ipanema.

It all turned out okay in week one. Even when the drug-crazed guy approached us on the empty, drizzling beach it turned out okay. “I…need…money,” he said a few times.

We apologized that we didn’t speak Portuguese and asked him if he spoke Spanish. “Not Espanol, English!” he insisted, wild-eyed. “I…NEED…MONEY.”

We convinced ourselves we weren’t being mugged, exactly. He seemed convinced too because he let us get up and walk away and find another wet spot to enjoy the sun going down. It seemed Rio got the memo. If there could be no mention of girls in South America, there would have to be something else. It’s not the bikinis that move the pulse in Rio, but a more dangerous kind of tease. And it’s a great parlor trick to make someone happy by doing nothing to them at all.